|

|

Lee's Adventures on Semester at Sea ® AMAZON RAINFOREST

|

|

|

Introduction

|

Journal entry, February 14, 2003 I had to get up very early on the morning of February 6 for the Amazon trip. We departed at 5:30. I slept a bit on the plane, but not much. I never find it very easy to sleep on planes. Too many sounds and people walking up and down the aisles. We had a two-hour layover in Brasilia, the capital of Brazil. Then we boarded a plane for Manaus, a city of 1.8 million people in the center of the Amazon rain forest.

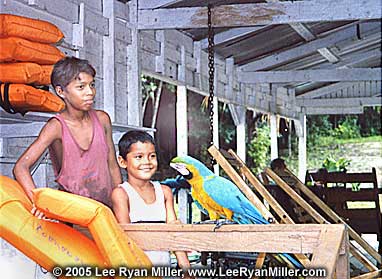

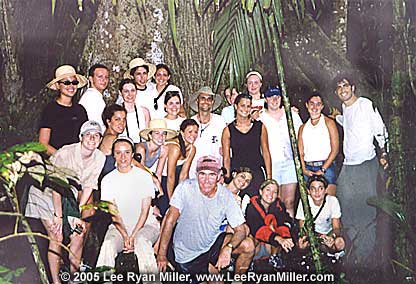

Upon arrival, we were met by our guides. We divided into three groups, and boarded separate buses. Each group had a faculty or staff member as trip leader. I was the leader of my group of twenty-three students. After a short bus ride, we arrived at our riverboat, the Vincador V. It was covered with brightly colored balloons, and some beautiful young women wearing very little clothing hung necklaces made of wooden beads and feathers around our necks. Several of us took pictures with the women. The river boat was very small. Two-thirds of the upper deck was taken up by twenty-five hammocks. There was a roof over the hammock area, and there were plastic tarps rolled up to close off the sides in the event of a strong rainstorm. The aft third of the upper deck was open, and often we sat there in the sun on plastic chairs. Down below were some more chairs and a long table. Meals were spread out on that table. You took what you wanted, and sat down on a chair, or on the deck if none were available. At night, the guides and crew slept on this deck. It also contained two bathrooms. Personal hygiene was rather awkward on the boat. We were told that you must drop any toilet paper in the wastebasket, rather than in the toilet. Stinky! But the baskets were emptied regularly. There was only one sink (so you had to be quick), and it was hooked up to river water. I usually remembered to brush my teeth with bottled water. I forgot a couple of times, but I didn’t get sick. No showers, aside for one out in the open on the deck. To get clean—a swim in the river or a strong rain shower were the favored options. There was no privacy. The hammocks were closely spaced. If you needed to change your clothes, you had to do as the surfers did back in Redondo Beach—wrap a towel around you and drop your pants, and then hoist up the new ones underneath. Our guides were fluent in English. Walter and Mathias were very nice. I would guess that their ages were somewhere between the students and mine—perhaps mid to late 20s. Walter was quite handsome, and the young women were all smitten with him. There were twenty-four people in our group, including me. The empty bed, I found out later, belonged to a young woman who had returned home soon after the ship had departed Nassau. She was quite ill with anorexia, I’m told. How sad that she was unable to join us for this adventure. We sailed to the “meeting of the waters” – the point where the Amazon and the Rio Negro converge. Both are wide rivers, but differ in character. The Amazon is brown with silt carried from its long eastward journey across the continent of South America. The Rio Negro is slightly acidic, our guides told us, and the leaves that fall into it turn the water black as they decompose. The “meeting of the waters” was quite beautiful. The water of the two rivers did not just mix, but instead swirled together, creating ever-changing marble patterns in black and brown. Freshwater dolphins—some pink, some gray—swam nearby. Our guides explained that there were fewer mosquitoes up the Rio Negro, and that was the way we headed, northward, toward Venezuela. We stopped off at an isolated settlement. A large extended family lived there. The matriarch was an old woman who claimed to have 18 children. She did not seem that old, perhaps sixty, and if what she said was true, she must have had her first child at a very young age. The inhabitants of this settlement mostly lived off the land, although they traded some goods to buy manufactured items, like knives. Their houses had no electricity or running water. But they lived right on the shore of the river, and the surrounding trees provided a bounty of foodstuffs and other valuable substances—mangoes, cocoa, coffee, gourds, rubber, etc. They also grew some vegetables and other crops. The old woman and an old man were tying bundles of some green leafy vegetable. Our guides explained that they would sell them in a market in Manaus.

I asked the guides whether the tour company paid them. He said that they paid them monthly to maintain the dock and allow tourists to visit their settlement. I don’t think they got paid very much, since they appeared rather poor by our standards. But they had a roof over their heads and plenty to eat, apparently. Next we went to see the giant water lilies. The lily pads were around a foot in diameter. We bought some souvenirs at a store selling handicrafts. We ate dinner on the ship. It was a buffet of salads, meats, fish, rice, and manioc. Manioc, a staple of the region, was served with every meal. It looked and tasted sort of like corn meal. After dinner, when it was plenty dark, we divided up into two groups and set off in motorized canoes. My canoe traveled close to the shore. Our guide shined a flashlight in the bushes lining the shore as we continued, hugging the shore. Suddenly we stopped and the guide jumped out of the canoe and dove into the bushes. He returned a moment later holding an alligator. It was nearly two feet in length. He told us that it was around two years old. When asked how he’d spotted it, he told us that the eyes shined when the beam of the flashlight struck them. He showed us many interesting features of the alligator. It has no tongue, but it has a valve at the back of the throat that closes it when it goes under water. Alligators breathe air; they do not have gills like fish. They have an inner set of transparent eyelids that help them to see better under water. Our guide “hypnotized” the reptile so that it lay still. He did this by laying it on its back and gently stroking its belly. According to our guide, alligators (and snakes) have lots of nerves on their bellies that enable them to feel the footsteps of approaching animals. Stroking their bellies stimulate these nerves and make them go limp.

He showed us how to hold the alligator safely (one hand clamped firmly on the neck, the other at the base of the tail. Each of us took a turn holding the alligator while someone else took our picture. Then the guide climbed down into the river and set the alligator free. It disappeared under the water. Afterwards we returned to the riverboat and found a sheltered cove in which to anchor for the night. We climbed into our hammocks. The guides explained that you need to lie on your back diagonally across the hammock. That was indeed the most comfortable position. If you try to lie straight, your back gets curled up. Diagonally, you can lie flat, and one side of the hammock rises, creating a wall for some privacy. I chatted a while with Megan, the young woman in the hammock on my left. We became friends on the trip, and she sometimes helped out with my administrative duties (like sorting the airline tickets). She was a student at Boston University. The hammock was fairly comfortable, but I did not sleep very much on this trip. The students often would talk until late into the night. They usually spoke softly, but packed as closely as we were, this kept me awake. Furthermore, most of the forest animals are nocturnal. More than once I woke up in the night to a chorus of hoots, whistles, and howls coming from the forest. It was like being in a movie. I was not scared by the sounds, except for one time before dawn when I heard splashing in the water. I imagined that it must be an enormous alligator swimming toward our boat. I looked over the side, and discerned the silhouette of a canoe. The pilot had been kind enough not to start the motor at that early hour. The sunrise on February 7 was a beautiful display of reds and oranges. Everyone else on the top deck was still asleep. I went down to use the bathroom before the rush. I gave myself a sponge bath with a washcloth and brushed me teeth before the first student descended the stairs. Breakfast consisted of a buffet of fruits, bread, eggs, and other assorted items. One unusual item was made from the dried juice of the manioc plant. Thin white sheets were rolled up and sliced. It had a buttery flavor. Most of the students did not like it. I thought it tasted okay. Also, they had prepared some sort of hot cereal, very milky and sweet. After breakfast we went hiking for several hours in the rainforest. I felt like I was in a jungle adventure movie. Above us stood a canopy of tall trees blocking out the sun, while dense foliage clung to us as we made our way down a narrow, muddy trail. I found it fascinating how the tiny leaf-cutter ants carried leaves many times their size. Our guides taught us some jungle survival skills, such as building a shelter, laying a snare for animals, finding water, making a fire without matches. For example, they told us that when we find a stream, we should get our drinking water upstream, wash a bit downstream, and clean any animals we catch further downstream. They pointed out a tree that has extremely flammable sap. One guide cut a notch in a stick and stuck it in the ground. Then he took a sharp, flat stone and cut into the bark of the tree. He stuck the stone in the notched stick and lit the stone on fire. Then he put the torch by the cut in the tree and a jet of flame sprouted from the trunk. It was very hot and humid in the rainforest. Some people cooled off by standing under a waterfall. I did not, because I didn’t want to hike back in wet clothes.

When we got back to the boat, we bathed in the river. Everyone put on their bathing suits and grabbed their shampoo and soap. It was very funny, but we all felt refreshed. Then we played with a football in the river. The men tossed the football back and forth, and the women tried to get it away from us. Then the women succeeded, and they tossed the ball back and forth until we men got it back. We had a great time tossing the ball, intercepting, and tackling one another until lunch. After lunch we visited a village on a hill overlooking the river. We had a big climb up an enormous flight of steps. Our guides explained that the river floods for several months at a stretch—in June and July, if I remember correctly—and much of the forest lies under water during that period. The silt renews the soil, but it makes habitation difficult. If one lives on higher ground, the soil is shallow, and the nutrients get depleted after just two or three years. People tend to clear new land by burning the vegetation. When we reached the top of the hill, we noticed an acre or so of land that was still smoldering. It was raining. The rain felt pleasant, given the heat and humidity. We walked along a muddy trail through the village to a hut in the back where a man was cooking manioc. There were lots of ants on the trail just before we reached the hut, and since most people were wearing sandals, many got bitten. I kept my feet moving quickly, and only one ant got on my feet. Fortunately I brushed it aside before it bit me. I heard many students cry out in pain. They said it felt like a bee sting. Afterwards, the trail circled back around to the village soccer field. We played a soccer game against the men of the village. They all had Brazilian soccer jerseys on. There were a lot more of us, and we kept rotating players in and out. Most people played barefoot (better than sandals). I played defense, but not very well. The ball got past me every time. But the villagers were very good players. They beat us badly. After the game, the villagers gave Brazilian soccer jerseys to some of our best players, and we presented them with a couple of soccer balls. After we returned to the riverboat, we gave the balloons adorning it to the kids in the village. I had a nice chat with two of the students, Alana and Kristina. They are best friends, and Alana is in my Politics of Global Inequality class. At their home college (a small college in Ohio) they are doing some sort of program focused on global inequality, and Alana was very interested in my class. Kristina is taking instead a class on development economics. That night we joined the other three boats and had a barbecue on the beach. I had a nice talk with the medics from the three boats. They were all medical students at a university in Manaus.

The following morning, Tim, one of the students on my boat, was sick with diarrhea. I gave him immodium from my first aid kit and the medic sat with him for the day. The rest of us went piranha fishing. The bait was chunks of raw meat. I caught three things: the bottom of the river, a tree, and my own shirt. Out of twenty-four SAS participants (divided between two canoes), only two young women caught piranhas. Alana, a vegetarian, was one of them. She apologized over and over to the fish. It was very funny. It turned out that the fish was too small, and the guide threw it back. But not before first letting us take pictures, and showing us its sharp teeth. A single piranha can bite your finger off, while a school of them can strip your bones of all their flesh in just a few minutes. The other young woman caught a larger piranha, and the cook prepared it that afternoon. We did not eat the piranha. Presumably the crew did. They took us to a lodge where we had lunch with the people from the other two riverboats. Each trip leader was asked to say a few words. I was greeted with loud cheers when I stood to speak. I thanked the students and guides. After all three of us had spoken, the guides gave stuffed piranhas (real stuffed fish, not fuzzy toy ones) as prizes to those who had caught fish. After lunch, just as we got aboard the boat, it started to rain. It was pouring hard. Everyone really wanted to take a shower, and had planned to use the open-air shower on the deck. This was much better. No waiting your turn. Everyone put on their bathing suits. We lathered up and rinsed off in the pouring rain. The women rinsed their hair more thoroughly with water that had collected in the plastic tarps. The rain cooled the weather down. When I dried off and dressed, it was cool enough for me to put on a sweatshirt. I had a nice chat with Isanne, our boat’s medic. She was a member of a spiritualist church in which mediums speak with spirits. Beth and I once visited a church of that sort while we were living in Las Vegas. It was quite interesting. Isanne was a very nice young woman. She never left Tim’s side that day. I think he appreciated the attention. Our visit was winding down. Our guides allowed us to buy our hammocks for $10. I bought mine. I thought I might hang it in the back yard. We sailed back to Manaus that evening. The city had its share of poor people and run-down buildings like elsewhere in Brazil, but seemed to lack the grinding poverty apparent in Salvador, Rio, and other major cities. Manaus is located in the middle of the rainforest, far from any other large cities, and some 800 miles from the sea. Despite this, it is a major port, and the river was crowded with container ships. Our guides explained that Manaus was something of a boom-town, and had a very low unemployment rate, unlike most other Brazilian cities, because of government tax incentives provided to lure lots of foreign investment. We first went to a club where we saw a show based on the Boi Bumba dance of the region. The dancers were great. They invited us onto the stage to dance with them. Perhaps half the SAS students did. I joined them, as did George Shur, the SAS assistant dean who had served as trip leader on one of the other riverboats. The students got a kick out of watching us dance on stage. After the show, we went to an outdoor blues club. It was located next to a skateboard park. It struck me as interesting that the people of Manaus seemed to be nocturnal. At midnight on a Saturday you might find Americans out at nightclubs. But I was surprised to see lots of people skateboarding—not to mention bicycling and jogging—at that hour. I suppose that they exercised at night to avoid the intense heat and humidity of the day. That was the only indication that Manaus lay in the middle of a tropical rainforest. Our flight departed at 2 a.m. on February 9. We had a two hour layover in Sao Paolo and arrived back in Salvador at around noon. I was thoroughly exhausted by the time I got back to the ship. I took a nap, got something to eat, and went for a stroll around Salvador for a little while. The ship departed that evening for Africa. Excerpt from an article I wrote for Stanislaus Connections Depending upon whom you ask, the Amazon rainforest is either a fantastic repository of biodiversity needing protection, or else a land of enormous natural resources that can lift millions of people out of poverty. Most inhabitants of rich countries hold the former view, while most Brazilians hold the latter. I left Brazil with a better understanding of both viewpoints. The majority of Brazilians live in such extreme poverty that getting enough to eat easily trumps environmental concerns. While I was enchanted by the beauty of the rainforest, I also recognized that it is unrealistic to expect the Brazilians to protect it from development when they see such development as their only means of survival. The only way to protect the Amazon rainforest is for the rich countries like the United States to pay for it. This will require enormous expenditures of money to create the sort of ecologically sustainable development that will both protect the rainforest and reduce the level of poverty in Brazil. Are the taxpayers in rich countries willing to pay for this? Only time will tell.

|

|

|

|

HOME | ABOUT DR. MILLER | POPULAR WORKS | SCHOLARLY WORKS | APPEARANCES | SEMESTER AT SEA | PHOTOS | CONTACT LEE |

|

|

|

Copyright ©

1998 - 2009 Lee Ryan Miller |