|

|

Lee's Adventures on Semester at Sea ® INDIA

|

|

|

Introduction |

Excerpt

from an article

I wrote for Stanislaus Connections As

the S.S. Universe Explorer approached India, there was great tension in

the world. Just a few weeks

earlier, Indian troops had massed on the border with Pakistan, and there

was a real danger of a nuclear war between these two countries.

Now, the American government was on the verge of invading Iraq.

We

were not insulated from these events.

While we were in Cuba, several students’ passports had been

stolen. Although the students

had been able to obtain new passports from the U.S. consulate during our

visit to Brazil, they had been unable to obtain new visas from the Indian

government. As a result of

tensions between the U.S. and Indian governments over the impending war in

Iraq, these students were not permitted to set foot ashore.

Furthermore, whenever we wished to disembark or board the ship, we

had to pass through a phalanx of Indian troops and have our identification

checked twice—by soldiers and by immigration officials. We

visited the port of Chennai, also known as Madras, a city of 4.5 million

inhabitants in southeastern India. We

arrived at dawn on March 15, 2003. It

took customs and immigration until afternoon to clear the ship.

Unlike other ports, they insisted on meeting with each passenger

individually to check his/her passport.

Afterwards,

we waited in line for hours to leave the ship.

The Indian officials had given each person a customs form and a

disembarkation form, and as we exited the ship, additional officials

scrutinized each form. Then

we walked about fifty yards to a checkpoint manned by soldiers.

They checked our papers as well.

Finally, when we reached the exit of the port, a third set of

guards checked our papers. Was

the Indian government nervous about threats to their national security

posed by a group of American college students and faculty, I wondered, or

was this some sort of elaborate jobs program?

On

the day we arrived in Chennai, I decided to explore the streets near the

port for an hour on foot. All

along the sidewalks were street vendors selling just about everything

imaginable. Food to clothing

to cell phones—it was all there. I

even saw a couple of men making keys.

Unlike in the US, however, they were sitting on the ground

duplicating keys by hand with a file. Beggars

were constantly coming up to me and asking for money.

Lots of them were kids. Vendors

were constantly trying to get me to buy their wares. But a smile and a polite “no thank you” was enough to

send them away. India

is not immune to globalization. At

one point, a little boy came up and started talking to me.

I assume he was speaking Tamil (the local language), and I did not

understand him. He was

wearing a Nike T-shirt. I

pointed to the Nike swoosh on his shirt and said, “Nike.”

Then I pointed to the swoosh on my own Nike T-shirt and said,

“Nike.” I pointed back

and forth between his T-shirt and mine, and he indicated his understanding

by smiling and shaking his head in Indian fashion.

Indians

often tend to shake their heads in a peculiar way that I’ve seen nowhere

else. They rapidly tip their

heads a couple of inches toward one shoulder, then the other, repeating it

several times in quick succession. As

far as I can tell, this means neither yes nor no, but instead merely that

they are listening to what you’re saying.

(Sort of like an American murmuring “uh-huh.”)

After

half an hour or so I turned down a side street and came back along a

street parallel to the one I had been following.

That street seemed to be mostly residential.

There were many people about, and most of the men were wearing

flat-topped, brim-less hats. I

heard chanting coming from a building along the street that appeared to be

a mosque. No one approached

to sell me anything or to beg. They

just stared at me. No one

smiled. I did not feel welcome.

At the next intersection, I went up a side street and returned to

the street I had been following earlier. A

few minutes later, a man came up to me and gave me a bear hug.

I had no idea what he was saying to me, and after he released me, I

continued walking. He did not

follow. A while later a man

grabbed my sunglasses, which were hanging on a band around my neck.

He put them on his own face, but since they were still connected to

me, the glasses immediately fell off, and bounced onto my chest.

Another man started shouting at the man who had taken my glasses. I

had no idea what they were saying, and I just kept walking. Soon,

I reached the port, and after passing through numerous security checks,

boarded the ship. Excerpt

from an article

I wrote for Stanislaus Connections Imagine

that you could take everything that has ever existed in human society and

toss it together like a salad. Then

you would have an inkling of what I experienced visiting India.

India is the heartland of Hinduism, the birthplace of the Buddha, a

land where you can visit a church built by one of Jesus’ apostles, the

country with the second largest Muslim population in the world.

There you find nuclear scientists and computer programmers amidst

people who scarcely live differently from their forebears thousands of

years ago. The smell of

incense mingles with the stench of raw sewage.

You must take your shoes off to visit an ancient temple where, just

beside you, you see cows—and children—defecating.

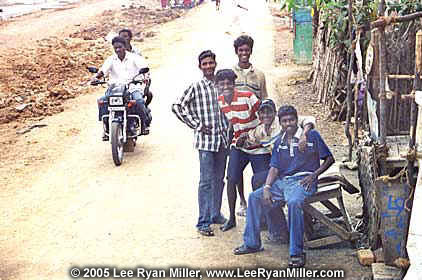

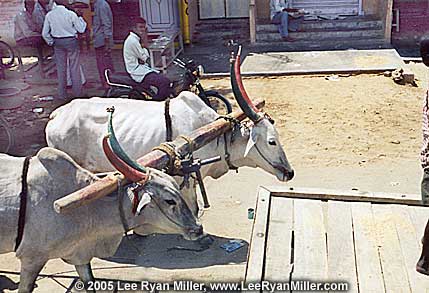

During

our visit to India, I spent most of my time in the port city of Chennai. However, on March 16, 2003, I went on a field trip to

Kancheepuram. Our motorcoach

left behind the city and passed through a number of poor but picturesque

villages where cars and motorcycles shared the muddy streets with

bicycles, cows, and carts drawn by oxen (the horns of which were painted

red, gold, and other bright colors).

The women wore colorful saris, yards of cloth draped around their

torsos and legs. Some men wore collared shirts with trousers; others just wore

some cloth wrapped around their waists like skirts; still others wore

nothing but skimpy loincloths. Between

villages were lots of rice paddies. Sometimes

I saw rickety shacks that did not appear fit for human habitation.

Other times I saw modern houses. We passed Hindu temples, Christian

churches, and Moslem mosques. I saw every sort of human endeavor, and

every sort of lifestyle imaginable. After

a couple of hours we arrived at our first destination, an ancient Hindu

temple in Kancheepuram called Sri Ekambaranthar.

A stone wall enclosed the temple grounds.

We entered via a corridor running through the center of a huge

stone tower. The tower was

covered with carvings of people and all sorts of creatures, real and

fantastic. To

approach the tower, we had to push our way through a crowd of men selling

leather sandals and other items, plus a crowd of beggars.

There were old women and children, plus people with missing limbs

and people with horrible deformities. Our guide warned us not to give to

the beggars, indicating that if we gave to one, the whole crowd would

encircle us, beseeching us for money.

It broke my heart to heed this warning.

Just

before entering the gate to the tower, we all removed our shoes and left

them with an attendant. As

I walked onward with my group, an old woman grabbed me by the hand and

dragged me over to the wall, where there was an alcove containing a stone

dish on a pedestal. The woman

pried open my hand and dropped in a fistful of white grains.

She pantomimed that I should toss it onto the plate.

I complied, and she blessed me, and all my family.

Then she demanded that I pay her 200 rupees (about $4). I

refused and walked away. I

did not like the idea of a stranger forcing me to do something I didn’t

want to do in the first place and then demanding that I pay her for it.

She ran after me demanding that I pay her, but I ignored her, and

she gave up once I reached my group.

We

crossed an open area and entered the gate into the inner temple grounds. Inside were lots of statues.

To the left lay the entrance to the main temple building.

Straight ahead was a staircase leading down to a square pool of

water, perhaps twenty feet wide. Another woman grabbed my hand and dragged me toward the pool.

“Poojah,”

she said. “No,

thank you,” I replied. “No

money, poojah,” she insisted. “No,

thanks,” I persisted. “No

money, no money, poojah,” she insisted. I

gave up and stopped resisting. The

woman led me down the steps to the edge of the pool.

She told me to open my hands and she dumped in a small basket of

white grains. She

communicated by a combination of broken English and gestures.

She told me to toss the grain into the pool. “Fish,”

she said, pointing. Fish

surfaced and ate the grain. The

woman dumped another basket of grain into my hands and I tossed it to the

fish. She repeated this until

four baskets of grain were exhausted.

Then she splashed some water on my head, and blessed me and my

family. Finally, she demanded 200 rupees. She had insisted “no money” repeatedly, and I was annoyed at her deception. A man who spoke better English than she did told me that the woman was requesting a donation to the temple. I was pretty sure that it was a donation to the woman, rather than to the temple, but I figured that I probably owed her something for allowing me to feed the fish. So I gave her the money. I climbed up the stairs and re-joined my group, wondering why the old women had accosted only me. We

went inside the temple. The

place smelled like a combination of incense and melted butter.

There were all sorts of statues inside, elaborately carved pillars,

carvings on the walls, etc. We

were permitted to go everywhere except for the inner sanctum, which

contained the lingham, a stone pillar representing the penis of the god

Shiva, one of the three main gods of Hinduism (the others being Brahma and

Vishnu). We

were permitted to visit the “festival altar,” which was a golden

statue. On either side were mirrors facing one another, creating the

illusion of infinity. I

dropped some coins on a plate. The

priest placed a stone helmet on my head and blessed me.

He offered to rub some holy ashes on my forehead, but I declined.

Our guide indicated that the ashes were the remains of burnt dung

from cows that wander around the temple compound. In

a courtyard at the center of the temple grew a huge mango tree.

Our guide told us that the tree was 2500 years old.

She said that a god and goddess had been married under that tree. As

we crossed the temple grounds, heading for the exit, I noticed several

cows wandering about. I also

saw a child defecating on the ground.

I realized that ritual purity and cleanliness were distinct and

separate concepts to Hindus. I

retrieved my sneakers. My

socks were black. I put on my

sneakers, pushed my way through the crowd, and boarded the bus.

I felt simultaneously repulsed and fascinated by this alien

culture. Excerpt

from a journal entry dated March 17, 2003 We

drove to another, smaller temple that was under renovation.

Artisans were redoing the carvings on the walls.

There were dozens of alcoves for meditation.

But there were no worshipers or meditators, because the temple was

under renovation. It was a

lot cleaner than the temple we had visited earlier. We

ate lunch at a hotel restaurant. The

Indian food was great.

Then

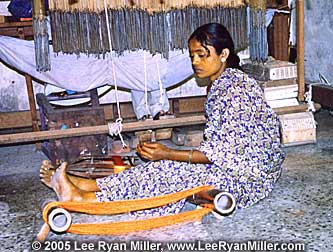

we visited a silk factory. Kancheepuram

is famous for its hand-woven silk. We

watched a woman spinning the silk into thread, and people with looms

weaving the thread into cloth. The

looms were powered by hand, and the mechanisms were guided by a pattern of

dots punched out of pieces of cardboard. (I guess they ran sort of like

old punch card computers). I

also looked at the showroom. The

silk saris were beautiful. I

bought a sari for Beth, as well as a dhoti (white cotton shirt and pants)

for me. We

next drove to Mahaballipuram. This

is the modern name of Mamallapuram, which was once a seaside fishing

village named after a king who was a great wrestler.

In the 7th century, a king had ordered temples and

statues and bas reliefs carved from massive rock faces and boulders.

The dynasty fell before the work was completed, and the temples

were never used. The work was

beautiful. Whenever

we got out of the bus, we were mobbed by people selling all sorts of

souvenirs. They were very

aggressive, and it was virtually impossible to shake them until we entered

areas where entry was restricted to those who’d paid for a ticket. I am

normally pretty patient with such things while traveling, but the weather

was unbearably hot and muggy; quickly my replies of “no thank you”

turned into a simple “no, no, no!” We

drove along the coast on the way home.

It was a pretty drive. There

were many huge houses on the seashore, in stark contrast to the wretched

huts we often saw nearby them. I

had planned to visit the family of Srikant Ramaswami, a good friend from

college. I’d tried calling

them without success soon after I arrived in India.

When I got back to port, I tried calling the Ramaswamis again. Still no answer. I

boarded the ship and checked my mailbox.

Pat Danylyshyn-Adams, who was serving as duty dean that day, had

left me a message. Mr.

Ramaswami had called and left a corrected phone number.

The number I’d been calling was off by one digit. I

grabbed dinner before the cafeteria closed, took a quick shower, and then

disembarked. I walked to a

small business in the port area that provides telephone service.

They had a couple of phones from which one could make international

calls for a fee of 25 rupees per minute, which is about 50 cents.

That is quite a good price, especially given that they charge

something like $10 per minute for calls from the ship.

I had called my wife, Beth, previously, and they let me make the

local call for free. Mr.

Ramaswami said he would pick me up from the US consulate the following day

sometime between 10:30 and 11:00 a.m. and bring me to his home. I

left the phone service shop, boarded the ship, and went to sleep. Excerpt

from an article

I wrote for Stanislaus Connections

India

is a crowded place, with a population exceeding 1 billion.

Nowhere is this more apparent than on the roads.

On my first day in Chennai, I took a taxi.

A couple of colleagues had an errand to run, and they invited me to

come along for the ride. I

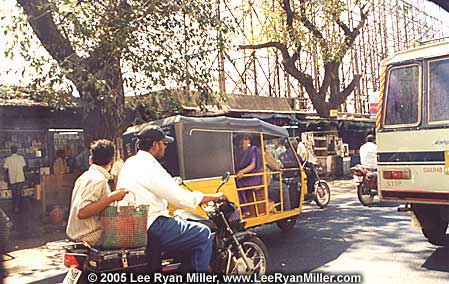

probably should clarify the various types of vehicles one can hire.

Bicycle rickshaws are becoming rare.

I only saw them shuttling people from the ship to the port exit.

Outside the port exit, there were countless auto-rickshaws.

These vehicles, called “autos” by the locals, are three-wheeled

vehicles with the sides open to the air. One

can also hire a taxi, which is similar to a taxi in the US, except that

you have to negotiate the price, rather than being charged by the meter. There

is no equivalent to renting a car in Chennai.

The closest would be what the locals call hiring a car.

The car comes with a driver, and is at your disposal for a set

period of time—usually five hours or ten hours.

An auto costs only about $2 dollar per hour. A taxi costs about twice that.

A car costs about $10 per hour. Taxis

and cars are usually Ambassadors. These

are old-style cars with big fenders and running boards like those in use

in the US in the 1940s. They

are not that old, however. The

company that produces them just has not changed the design very much over

the years. The

driver of our taxi honked his horn every few seconds as he wove through

the traffic, often getting within inches of bicycles, pedestrians, and

other vehicles. All the other

drivers followed the same strategy, and the horns created quite a din.

There seemed to be no traffic laws.

The lines painted on the road indicating lanes seemed to be

meaningless ornamentation. Red lights seemed to have no significance

whatsoever. Drivers just

beeped their horns and kept going. Despite

the slow speed of traffic (we could not have been going faster than 20

miles per hour), I was amazed that there were no traffic accidents. I

got a good view of the city on this trip.

It was a peculiar amalgamation of modern, old-fashioned, and

primitive. There were modern office buildings, buildings dating from the

British colonial era, and shacks all mixed together. It was just as chaotic as the traffic. The

city was filthy. There was

trash everywhere. During my

visit, I noticed that if I went outside more than a few minutes, my skin

became covered with a coat of grime.

Worst of all, it smelled really bad.

Not everywhere, but when we crossed the river, it stank like a

sewer. The cab had no air

conditioning, and we had the windows rolled down, so I got a really good

whiff. The

taxi driver took us directly to a store of his choosing, explaining

something like “good shopping here.”

I assumed he got some sort of kickback for bringing customers to

this place. We had to demand

several times that he take us directly to our destination before he

reluctantly put the car back into gear and started going again.

There were additional unwanted stops before my colleagues completed

their errand and we returned to the ship. One

of my closest friends from college is Indian American.

His parents spend six months per year with him in New Jersey, and

the other six in Chennai. I

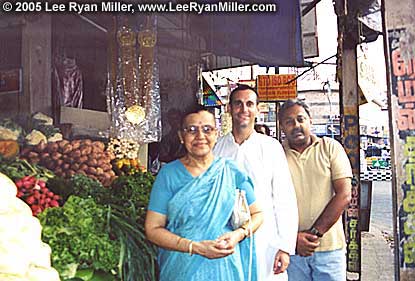

visited my friend’s parents, the Ramaswamis, while I was in Chennai. Mr.

Ramaswami, a retired engineer who had worked for an American multinational

corporation, asked me to meet him in front of the American consulate on

the morning of March 17. This

required me to arrange for transportation.

A

couple of days earlier, just after disembarking the ship, an auto-rickshaw

driver had offered me a ride. I

had declined, explaining that I had left the ship just to make a phone

call. (I wanted to call Mr.

Ramaswami to let him know I’d arrived.)

The man had handed me his cell phone and let me use it for free.

Afterwards, he gave me his phone number, and suggested that I call

him if I ever needed a ride. His

name was Joseph. On

March 17, I called up Joseph, and he met me outside the ship.

Unlike most of the other drivers, Joseph was dressed smartly in

slacks and a collared shirt. He

explained in decent English that he only drove his auto-rickshaw during

the day as a part-time job. At

night, he worked as an ambulance driver for the port. Joseph

drove me to the American consulate. This

experience was even more harrowing than the taxi ride.

The auto afforded a 360-degree view. Motorists were constantly driving between lanes or even on the

wrong side of the road in order to get ahead of one another.

I was white-knuckled a couple of times in anticipation of a head-on

collision with oncoming traffic. But

one driver or the other always swerved out of the way in time.

We

arrived safely at our destination in half an hour. After we reached the

consulate, Joseph let me use his cell phone to call Mr. Ramaswami.

Then he waited with me until Mr. Ramaswami arrived in a hired car

to pick me up. Joseph did all

this for just 100 rupees, or about $2.

To my astonishment, Mr. Ramaswami berated Joseph for overcharging

me. Excerpt

from a journal entry dated March 20, 2003 I

had a great time visiting with the Ramaswamis.

They treated me like a king. They

prepared wonderful Indian meals for me, and took me out to restaurants for

other wonderful meals. They

allowed me to call Beth back in the US, and to check my e-mail.

Every night they dropped me off back at the ship.

They took me shopping for gifts for family and friends.

They would not allow me to pay for anything except for the gifts

that I purchased. I really

hope that they will accept my offer to visit Beth and me in Modesto, so

that I can reciprocate.

Mr. and Mrs. Ramaswami are nearing the end of a six-month visit to Chennai. They were taking care of Mrs. Ramaswami’s elderly mother. On the alternate six months, Mrs. Ramaswami’s sister takes care of her. I

only saw Mr. Ramaswami on the first day, because he had to travel to

Bombay to take care of a matter involving some property he had inherited.

But Mrs. Ramaswami’s cousin Ram came every day to help out. Ram

was very kind and jovial fellow. His

grandfather had risen from humble beginnings to become the owner of a

major movie studio in Chennai. In

recent years, the family fortune has dwindled, and Ram seemed to be a

member of the middle class. It

was he who escorted me back to the ship each evening.

We had many interesting chats about politics, Indian society, and

other topics. Much

of my time with the Ramaswamis involved finding gifts for people back

home. Mrs. Ramaswami seemed

to enjoy the shopping. I

usually hate shopping, but it was a very interesting cultural experience.

For example, although it is possible to buy clothes “off the

rack,” it seems to be more common to have them made for you. I had picked out some silks for Beth, and Mrs. Ramaswami’s

tailors had them made into some beautiful outfits for Beth.

(This required me to call Beth a couple of times to get her

measurements.) Many purchases

involved Mrs. Ramaswami haggling to get a better price for me.

We went to a huge department store that sold only fabrics.

It consisted of several multi-storied buildings.

There were silks, cottons, blends—in all sorts of patterns and

colors. It was quite a feast

for the eyes. Excerpt

from an article

I wrote for Stanislaus Connections More

than half of Indians are illiterate, and 44% subsists on $1 or less per

day. Despite this, India has

a large and growing computer software industry, and is one of only a

handful of countries possessing nuclear weapons.

India is a land of remarkable contrasts. While

in Chennai, I spent several days visiting the family of an Indian American

friend. The Ramaswamis, a

middle-class Hindu family, owned a three-bedroom apartment in a pleasant

Chennai neighborhood. It was

located just one block from the Taj Hotel, one of the most luxurious

hotels in Chennai. A

block away in the opposite direction was a very poor, predominantly Muslim

neighborhood. There, people

wore dirty, shabby clothes and lived in shacks.

Cows roamed freely on the street.

The contrast was astounding. It

was just the next block, and it seemed to be a different world.

Mrs.

Ramaswami took me shopping to buy clothes for my wife, Beth.

Most Indian women have their clothes tailor-made, rather than

buying them off the rack. We visited a huge department store that sold

only fabrics. It consisted of

several multi-storied buildings. There

were silks, cottons, and blends—in every imaginable pattern and color.

It was quite a feast for the eyes.

I picked out some fabrics, and Mrs. Ramaswami’s tailors made them

into some beautiful outfits for Beth. One

day we had lunch at the home of G.V. Ramakrishna, my friend’s uncle.

Mr. Ramakrishna, a retired civil servant, lived with his wife in a

beautiful flat with marble floors. He

had served as ambassador to the European Union during the negotiations

leading up to the creation of the World Trade Organization. I found him to be extremely knowledgeable about nearly

everything under the sun. I

spent my nights on the ship. Shipboard

life in Chennai was different from most other ports.

We experienced water rationing.

Normally, while we were at sea, the crew purified seawater for

drinking and washing. While

in port they usually brought on water from land and purified it to

supplement the water supplies. The

water in Dar es Salaam and Chennai was so dirty, however, that the captain

hadn’t felt confident that it would be safe— even if purified.

So while in port, the taps flowed for just a four-hour period twice

per day (6:00–10:00 a.m. and p.m.).

When it did flow, it tasted awful.

Decent drinking water was available only at specified locations.

It was extremely hot and dirty in Chennai, and on a couple of

occasions, I greatly regretted having gotten back to the ship too late to

take a shower.

March

19 was my final day in Chennai. I

spent the morning on a field trip to a public housing project.

Our coach followed a road along the beach, alongside which we could

see the slums that housed poor fishermen.

Chennai followed the pattern of most other cities in the Developing

World: poor people migrate in

large numbers each year from rural areas to Chennai. They have helped to

swell the city’s population to six million residents. The newcomers

usually cannot afford apartments; they build huts from mud, scraps of

wood, and palm fronds on vacant land.

Life in these slums is dangerous, subject to disease, fires,

floods, and crime. The

government of Tamil Nadu, the state where Chennai is located, has a Slum

Clearance Board responsible for addressing the problems of the slums. They approach the problems in many ways.

For example, they have provided corrugated roofs for many of the

dwellings in the slums (palm frond roofs tend to catch fire), and have

provided electricity and water hook-ups.

They also have built many public housing projects and have

resettled the slum dwellers into these projects.

Many of these programs receive funding from the Indian national

government.

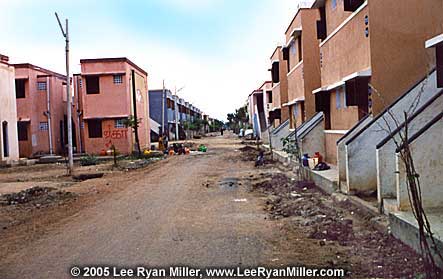

The

public housing project we visited was fairly new.

It had been built on a swamp that was filled with about 8 feet of

dirt in advance of construction. The

first phase of the project was completed in 2001.

They are building around 3000 apartments per year, and at the time

of our visit, the project housed around 7000 families.

The residents had formerly occupied slums that were slated for

demolition by the government in order to build infrastructure projects

like a railroad and a canal. Our

guide indicated that their income was around 400-800 rupees ($8-16) per

month. The residents were

required to pay 150 rupees per month of rent for twenty years, after which

they are to be given ownership of their apartments.

Our guide told us that the rent is insufficient to meet expenses,

and that the project is subsidized greatly by the government. This

enormous project had a few public facilities.

There was a community center that the residents were permitted to

rent for a nominal fee for weddings and other events.

There also was a primary school and a vocational training center,

and a couple of small shops. When

we visited the vocational training center, there were some women weaving

baskets, and there were a few computers. The

apartments themselves looked nice from the outside, but were very

depressing on the inside. An

apartment basically consisted of a single dark, square concrete room,

perhaps a dozen feet wide. An

entire family lived, cooked, and slept in this space.

It was hot outside, and even hotter inside the apartments.

The

residents had electricity, but no running water or phones.

Every two apartments shared a toilet, and water was retrieved from

a few taps on the street. Our

guide assured us that these people’s lives were considerably better in

this place than they had been in the slums.

I found the conditions in the project to be quite wretched, and I

can only imagine what conditions must be like in the slums.

|

|

|

|

HOME | ABOUT DR. MILLER | POPULAR WORKS | SCHOLARLY WORKS | APPEARANCES | SEMESTER AT SEA | PHOTOS | CONTACT LEE |

|

|

|

Copyright ©

1998 - 2009 Lee Ryan Miller |